Oromia

Oromia

Oromiyaa | |

|---|---|

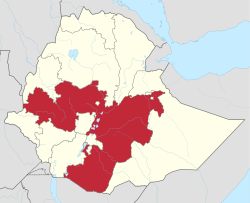

Map of Ethiopia showing Oromia | |

| Country | |

| Official language | Oromo |

| Capital | Addis Ababa |

| Government | |

| • Chief Administrator | Shimelis Abdisa (Prosperity Party) |

| Area | |

• Total | 353,690 km2 (136,560 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 1st |

| Population (2017) | |

• Total | 35,467,000[1] |

| • Rank | 1st |

| • Density | 100.267/km2 (259.69/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Oromo or Oromian |

| Time zone | EAT |

| ISO 3166 code | ET-OR |

| HDI (2021) | 0.482[2] low · 8th of 11 |

Oromia (Oromo: Oromiyaa) is a regional state in Ethiopia and the homeland of the Oromo people.[3] Under Article 49 of Ethiopian Constitution, the capital of Oromia is Addis Ababa, also called Finfinne. The provision of the article maintains special interest of Oromia by utilizing social services and natural resources of Addis Ababa.[4]

It is bordered by the Somali Region to the east; the Amhara Region, the Afar Region and the Benishangul-Gumuz Region to the north; Dire Dawa to the northeast; the South Sudanese state of Upper Nile, Gambela Region, South West Ethiopia Region, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region and Sidama Region to the west; the Eastern Province of Kenya to the south; as well as Addis Ababa as an enclave surrounded by a Special Zone in its centre and the Harari Region as an enclave surrounded by East Hararghe in its east.

In August 2013, the Ethiopian Central Statistics Agency projected the 2017 population of Oromia as 35,467,001;[1] making it the largest regional state by population. It is also the largest regional state covering 353,690 square kilometres (136,560 sq mi)[5]

History

The Oromo people are one of the oldest Cushitic peoples inhabiting the Horn of Africa. There is still no reliable estimate of the history of their settlement in the region, however, many indications suggest that they have been living in the north of Kenya and south-east Ethiopia for more than 7,000 years, until the great expansion in 1520 when they expanded to the south-west and some areas in the north.[citation needed]

The Oromo remained independent until the last quarter of the 19th century,[6] when they lost their sovereignty. From 1881 to 1886, Emperor Menelik II conducted several unsuccessful invasion campaigns against their territory. The Arsi Oromo demonstrated fierce resistance against this Abyssinian conquest,[7] putting up stiff opposition against an enemy equipped with modern European firearms. They were ultimately defeated in 1886.[7]

In the 1940s some Arsi Oromo together with people from Bale province joined the Harari Kulub movement, an affiliate of the Somali Youth League that opposed Amhara Christian domination of Hararghe. The Ethiopian government violently suppressed these ethno-religious movements.[8][9][10] During the 1970s the Arsi formed alliances with Somalia.[11]

In 1967, the imperial regime of Haile Selassie I outlawed the Mecha and Tulama Self-Help Association (MTSHA), an Oromo social movement, and conducted mass arrests and executions of its members. The group's leader, Colonel General Tadesse Birru, who was a prominent military officer, was among those arrested.[12] The actions by the regime sparked outrage among the Oromo community, ultimately leading to the formation of the Oromo Liberation Front in 1973.[13] The Oromos perceived the rule of Emperor Haile Selassie as oppressive, as the Oromo language was banned from education and use in administration,[14][15][16] and speakers were privately and publicly mocked.[17][18] The Amhara culture dominated throughout the eras of military and monarchic rule.

Both the imperial and the Derg government relocated numerous Amharas into southern Ethiopia, including the present day Oromia region, in order to alleviate drought in the north of the country.[19] They also served in government administration, courts, church and even in school, where Oromo texts were eliminated and replaced by Amharic.[20] Further disruption under the Derg regime came through the forced concentration and resettlement of peasant communities in fewer villages.[21] The Abyssinian elites perceived the Oromo identity and languages as opposing the expansion of an Ethiopian national identity.[22]

In the early 1990s, the Ethiopian Democratic People's Republic began to lose its control over Ethiopia. The OLF failed to maintain strong alliances with the other two rebel groups at the time: the Eritrean People's Liberation Front (EPLF) and the Tigray People's Liberation Front (TPLF).[23] In 1990, the TPLF created an umbrella organization for several rebel groups in Ethiopia, the Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). The EPRDF's Oromo subordinate, the Oromo People's Democratic Organization (OPDO) was seen as an attempted replacement for the OLF.[citation needed]

On 28 May 1991, the EPRDF seized power and established a transitional government. The EPRDF and the OLF pledged to work together in the new government; however, they were largely unable to cooperate, as the OLF saw the OPDO as an EPRDF ploy to limit their influence.[23][24] In 1992, the OLF announced that it was withdrawing from the transitional government because of "harassment and [the]assassinations of its members". In response, the EPRDF sent soldiers to destroy OLA camps.[citation needed] Despite initial victories against the EPRDF, the OLF were eventually overwhelmed by the EPRDF's superior numbers and weaponry, forcing OLA soldiers to use guerrilla warfare instead of traditional tactics.[25] In the late 1990s, most of the OLF's leaders had escaped Ethiopia, and the land originally administered by the OLF had been seized by the Ethiopian government, now led by the EPRDF.[26]

Prior to the establishment of present-day Addis Ababa the location was called Finfinne in Oromo, a name which refers to the presence of hot springs. The area was previously inhabited by various Oromo clans.[27]

In 2000, Oromia's capital was moved from Addis Ababa to Adama.[28] Because this move sparked considerable controversy and protests among Oromo students, the Oromo Peoples' Democratic Organization (OPDO), part of the ruling EPRDF coalition, on 10 June 2005, officially announced plans to move the regional capital back to Addis Ababa.[29]

Further protests sparked on 25 April 2014, against the Addis Ababa Master Plan,[30] then resumed on 12 September 2015 and continued into 2016, when renewed protests broke out across Ethiopia, centering around the Oromia region. Dozens of protesters were killed in the first days of the protests and internet service was cut in many parts of the region.[31] In 2019, the Irreecha festival was celebrated in Addis Ababa after 150 years of being banned.[32][33]

Geography

Oromia includes the former Arsi Province along with portions of the former Bale, Illubabor, Kaffa, Shewa and Sidamo provinces.[citation needed] Oromia shares a boundary with almost every region of Ethiopia except for the Tigray Region. These boundaries have been disputed in a number of cases, most notably between Oromia and the Somali Region. One attempt to resolve the dispute between the two regions was the October 2004 referendum held in about 420 kebeles in 12 districts across five zones of the Somali Region. According to the official results of the referendum, about 80% of the disputed areas have fallen under Oromia administration, though there were allegations of voting irregularities in many of them.[34] The results led over the following weeks to minorities in these kebeles being pressured to leave. In Oromiya, estimates based on figures given by local district and kebele authorities suggest that 21,520 people have become internally displaced persons (IDPs) in border districts, namely Mieso, Doba, and Erer in the West Hararghe Zone and East Hararghe Zones. Federal authorities believe that this number may be overstated by as much as 11,000. In Doba, the Ministry of Federal Affairs put the number of IDPs at 6,000. There are also more than 2,500 displaced persons in Mieso.[35] In addition, there were reports of people being displaced in the border area of Moyale and Borena zones due to this conflict.[36]

Towns in the region include Adama, Ambo, Asella, Badessa, Bale Robe, Bedele, Bishoftu, Begi, Bule Hora, Burayu, Chiro, Dembidolo, Fiche, Gimbi, Goba, Haramaya, Holeta, Jimma, Koye Feche, Metu, Negele Arsi, Nekemte, Sebeta, Shashamane and Waliso, among many others.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1994 | 18,732,525 | — |

| 2007 | 26,993,933 | +44.1% |

| 2015 | 33,692,000 | +24.8% |

| source:[37] | ||

At the time of the 2007 census conducted by the Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (CSA), Oromia region had a total population of 26,993,933, consisting of 13,595,006 men and 13,398,927 women;[38] urban inhabitants numbered 3,317,460 or 11.3% of the population. With an estimated area of 353,006.81 square kilometres (136,296.69 sq mi), the region had an estimated population density of 76.93 inhabitants per square kilometre (199.2/sq mi). For the entire region 5,590,530 households were counted, which resulted in an average for the region of 4.8 persons to a household, with urban households having on average 3.8 and rural households 5.0 people. The projected population for 2017 was 35,467,001.[1]

In the previous census, conducted in 1994, the region's population was reported to be 17,088,136; urban inhabitants number 621,210 or 14% of the population.[citation needed]

According to the CSA, as of 2004[update], 32% of the population had access to safe drinking water, of whom 23.7% were rural inhabitants and 91.03% were urban.[39] Values for other reported common indicators of the standard of living for Oromia as of 2005[update] include the following: 19.9% of the inhabitants fall into the lowest wealth quintile; adult literacy for men is 61.5% and for women 29.5%; and the regional infant mortality rate is 76 infant deaths per 1,000 live births, which is about the same as the nationwide average of 77; at least half of these deaths occurred in the infants' first month of life.[40]

Ethnic groups

| Ethnic group | 1994 Census[41] | 2007 Census[42] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oromo | 15,709,474 | 85% | 23,708,767 | 88% |

| Amhara | 1,684,128 | 9% | 1,943,578 | 7% |

| Other ethnic groups | 1,080,218 | 6% | 1,341,588 | 5% |

| Total population | 18,473,820 | 26,993,933 | ||

Religion

| Religion (entire region) | 1994 Census[43] | 2007 Census[44] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muslim | 8,178,058 | 44% | 12,835,410 | 48% |

| Orthodox Christians | 7,621,727 | 41% | 8,204,908 | 30% |

| Protestant Christians | 1,588,310 | 9% | 4,780,917 | 18% |

| Waaqeffanna | 778,359 | 4% | 887,773 | 3% |

| other religious groups | 307,366 | 2% | 284,925 | 1% |

| Total population | 18,473,820 | 26,993,933 | ||

| Religion (urban areas) | 1994 Census[43] | 2007 Census[44] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orthodox Christians | 1,330,301 | 68% | 1,697,495 | 51% |

| Muslim | 471,462 | 24% | 990,109 | 30% |

| Protestant Christians | 137070 | 7% | 580,562 | 18% |

| other religious groups | 23,971 | 1% | 49,294 | 1% |

| Total population | 1,962,804 | 3,317,460 | ||

Languages

Oromo is written with Latin characters known as Qubee, only formally adopted in 1991[45] after various other Latin-based orthographies had been used previously.

Oromo is one of the official working languages of Ethiopia[46] and is also the working language of several of the states within the Ethiopian federal system including Oromia,[47] Harari and Dire Dawa regional states and of the Oromia Zone in the Amhara Region. It is a language of primary education in Oromia, Harari and of the Oromia Zone in the Amhara Region. It is used as an internet language for federal websites along with Tigrinya.[48]

There are more than 33.8% Oromo speakers in Ethiopia and it is considered the most widely spoken language in Ethiopia.[47] It is also the most widely spoken Cushitic language and the fourth-most widely spoken language of Africa, after Arabic, Hausa and Swahili languages.[49] Forms of Oromo are spoken as a first language by more than 35 million Oromo people in Ethiopia and by an additional half-million in parts of northern and eastern Kenya.[50] It is also spoken by smaller numbers of emigrants in other African countries such as South Africa, Libya, Egypt and Sudan. Besides first language speakers, a number of members of other ethnicities who are in contact with the Oromo speak it as a second language. See, for example, Harari, Omotic-speaking Bambassi and the Nilo-Saharan-speaking Kwama in northwestern, eastern and south Oromia.[51]

Economy

Oromia is a major contributor to Ethiopia's main exports - gold, coffee, khat and cattle. Lega Dembi in Guji Zone, owned by MIDROC has exported more than 5000 kilograms of gold,[52] followed by Tulu Kapi gold deposit in West Welega Zone.[53] Awoday in East Hararghe Zone is the biggest market of khat exporting to Djibouti and Somalia.[54] Oromia also has more abundant livestock than any other region of Ethiopia, including camels. It is also the largest producer of cereals and coffee.

The CSA reported that, from 2004 to 2005, 115,083 tons of coffee were produced in Oromia, based on inspection records from the Ethiopian Coffee and Tea Authority. This represents 50.7% of the total production in Ethiopia. Farmers in the Region had an estimated total of 17,214,540 cattle (representing 44.4% of Ethiopia's total cattle), 6,905,370 sheep (39.6), 4,849,060 goats (37.4%), 959,710 horses (63.25%), 63,460 mules (43.1%), 278,440 asses (11.1%), 139,830 camels (30.6%), 11,637,070 poultry of all species (37.7%), and 2,513,790 beehives (57.73%).[55]

According to a March 2003 World Bank publication, the average rural household has 1.14 hectares of land compared to the national average of 1.01 hectares. 24% of the population work in non-farm related jobs compared to the national average of 25%.[56]

Educational institutions

- Adama University

- Ambo University

- Arsi University

- Dambi Dollo University[57]

- Dandii Boruu University College

- Haramaya University

- Jimma Teachers College

- Jimma University

- Madda Walabu University

- Mattu University[58]

- New Generation University College

- Oda Bultum University [59]

- Oromia State University[60]

- Rift Valley University College

- Wollega University

- Awash Valley University

List of Chief Administrators of Oromia Region

| Tenure | Portrait | Incumbent | Affiliation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992–1995 | Hassen Ali | OPDO | ||

| 1995 – 24 July 2001 | Kuma Demeksa | OPDO | ||

| July 2001 – October 2001 | Position vacant | |||

| 28 October 2001 – 6 October 2005 | Junedin Sado | OPDO | ||

| 6 October 2005 – September 2010 | Abadula Gemeda | OPDO | ||

| September 2010 – 17 February 2014 | Alemayehu Atomsa | OPDO | ||

| 27 March 2014 – 23 October 2016 | Muktar Kedir | OPDO | ||

| 23 October 2016 – 18 April 2019 |  |

Lemma Megersa | OPDO/ODP | |

| 18 April 2019 – present |  |

Shimelis Abdisa | ODP/PP |

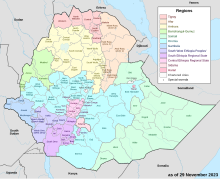

Administrative zones

Oromia is subdivided into 21 administrative zones,[61][62] in turn divided into districts (weredas).

| Number | Zone | Area in km2 |

Population estimate 2022[63] |

Administrative capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Arsi Zone | 19,825.22 | 3,894,248 | Asela |

| 2 | Bale Zone | 43,690.56 | 2,073,381 | Bale Robe |

| 3 | Borena Zone | 45,434.97 | 1,402,530 | Yabelo |

| 4 | Buno Bedele Zone | Bedele | ||

| 5 | East Hararghe Zone | 17,935.40 | 3,954,416 | Harar |

| 6 | East Shewa Zone | 8,370.90 | 2,126,152 | Adama |

| 7 | East Welega Zone | 12,579.77 | 1,806,001 | Nekemte |

| 8 | Guji Zone | 18,577.05 | 2,030,667 | Negele Borana |

| 9 | Horo Guduru Welega Zone | 8,097.27 | 840,709 | Shambu |

| 10 | Illu Aba Bora Zone | 15,135.33 | 1,861,919 | Metu |

| 11 | Jimma Zone | 15,568.58 | 3,568,782 | Jimma |

| 12 | Kelam Welega Zone | 9,851.17 | 1,166,694 | Dembidolo |

| 13 | North Shewa Zone | 10,332,48 | 2,100,331 | Fiche |

| 14 | Southwest Shewa Zone | 6,508.29 | 1,640,751 | Waliso |

| 15 | West Arsi Zone | 11,776.72 | 2,929,894 | Shashamane |

| 16 | West Guji Zone[64] | Bule Hora | ||

| 17 | West Hararghe Zone | 15,065.86 | 2,725,156 | Chiro |

| 18 | West Shewa Zone | 14,788.78 | 3,042,005 | Ambo |

| 19 | West Welega Zone | 10,833.19 | 1,987,182 | Gimbi |

| 20 | Oromia Special Zone Surrounding Finfinne | Finfinne |

See also

- Barchaa, cultural custom and social relations

Notes

References

- ^ a b c Population Projection of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2014 – 2018. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2018.

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- ^ "Oromia Region, Ethiopia". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ "UNPO: Oromo: Capital Addis Ababa Eludes Oromia State". unpo.org. 2 November 2009. Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Research on Covid-19 Responses and its Impact on Minority and Indigenous Communities in Ethiopia (PDF), September 2020

- ^ Ali-Dinar, Ali B. (26 May 1995). "Facts about the Oromo of East Africa". africa.upenn.edu. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania - African Studies Center. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ a b Haji, Abbas. "Arsi Oromo Political and Military Resistance Against the Shoan Colonial Conquest (1881-6)" (PDF). Journal of Oromo Studies. II (1–2). Oromo Studies Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 14 June 2011.

- ^ Ibrahim, Abadir M. (2016). "Religion-State Identification and Religious Freedom in Ethiopia". In Coertzen, Pieter; Green, M. Christian; Hansen, Len (eds.). Religious Freedom and Religious Pluralism in Africa: Prospects and Limitations. Sun Press. p. 443. ISBN 9781928357032. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Ibrahim, Abadir M. (2016). The Role of Civil Society in Africa's Quest for Democratization. Heidelberg: Springer. p. 134. ISBN 9783319183831. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Østebø, Terje (2011). Localising Salafism: Religious Change Among Oromo Muslims in Bale, Ethiopia. Leiden: Brill. p. 192. ISBN 978-90-04-18478-7. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Ali, Mohammed (1996). Ethnicity, Politics, and Society in Northeast Africa: Conflict and Social Change. Lanham, MD: University Press of America. p. 141. ISBN 978-07-61-80283-9. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Adejumobi, Saheed (2007). History of Ethiopia. United States of America: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-313-32273-0.

- ^ "Insurrection and invasion in the southeast, 1963-78" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Davey, Melissa (13 February 2016). "Oromo Children's Books Keep Once-Banned Ethiopian Language Alive". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Oromo" (Brochure). nalrc.indiana.edu. Bloomington, Indiana: National African Language Resource Center. n.d. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Ethiopians: Amhara and Oromo". iimn.org. St. Paul, MN: International Institute of Minnesota. 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) (12 February 2015). "Oromo". unpo.org. Brussels, Belgium: Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Omura, Susan; Mamo Argo; Teshome Bayu; Meti Duressa; Sheiko Nagawo; Taha Roba (1 February 1994). "Oromo". ethnomed.org. Seattle, WA: Ethnomed. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ United States Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services (1 March 1993). "Ethiopia. Status of Amharas". refworld.org. United Nations High Commission for Refugees. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Oromo Continue to Flee Violence". Cultural Survival Quarterly Magazine. No. 5–3. Cambridge, MA: Cultural Survival. September 1981. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Mulugeta Gashaw; Zelalem Bekele; Minilik Tibebe (June 1996). "Adele Keke, Kersa Woreda, Harerghe" (PDF). Ethiopian Village Studies: 3–21. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Bulcha, Mekuria (1997). "The Politics of Linguistic Homogenization in Ethiopia and the Conflict over the Status of 'Afaan Oromoo'". African Affairs. 96 (384). OUP: 325–352. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a007852. JSTOR 723182. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b 30 YEARS OF WAR AND FAMINE IN ETHIOPIA (PDF), September 1991

- ^ Ethiopia: Accountability past and present: Human rights in transition, 1 April 1995

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld | Chronology for Oromo in Ethiopia". Refworld.

- ^ "Genocide against the Oromo people of Ethiopia?". Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ Dandena Tufa (2008). "Historical Development of Addis Ababa: Plans and Realities". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. XLI (1–2): 30. JSTOR 41967609. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Yohannes Mekonnen (2013). Ethiopia: the Land, its People, History and Culture. Washington, DC: New Africa Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-9987160242. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Chief Administrator of Oromia says decision to move capital city based on study". Walta Information Center. 11 June 2005. Archived from the original on 13 June 2005. Retrieved 25 February 2006.

- ^ Ethiopia: Brutal Crackdown on Protests, 5 May 2014, retrieved 5 May 2014

- ^ Horne, Felix (15 June 2016), "Such a Brutal Crackdown Killings and Arrests in Response to Ethiopia's Oromo Protests", Human Rights Watch

- ^ "In Pictures: Ethiopia's Oromos celebrate Irreecha festival". Al Jazeera. 6 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- ^ Dahir, Abdi Latif (7 October 2019). "Ethiopia's Oromos Mark Thanksgiving Festival in Addis Ababa for the First Time in 150 Years". Quartz Africa. New York City: Quartz Media, Inc. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ "Somali-Oromo border referendum of December 2004" Archived 30 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre website (accessed 11 February 2009)

- ^ "Regional Overview: Oromia Region", Focus on Ethiopia (April 2005), p. 5 (accessed 11 February 2009)

- ^ "Regional Update: Oromiya", Focus on Ethiopia Archived 5 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine (May 2005), p. 5 (accessed 11 February 2009)

- ^ "Ethiopia: Regions, Major Cities & Towns - Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". citypopulation.de.

- ^ Samia Zekaria (2007). "Table 2.9 Population by Urban-Rural Residence, Sex, and Single Years of Age: 2007". The 2007 Population and Housing Census of Ethiopia: Statistical Report at National Level. Addis Ababa: Central Statistics Agency. p. 71.

- ^ "Households by sources of drinking water, safe water sources" (PDF). CSA Selected Basic Welfare Indicators. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ Ethiopia Atlas of Key Demographic and Health Indicators, 2005 (PDF). Calverton: Macro International. 2008. pp. 2, 3, 10. Retrieved 28 January 2009.

- ^ "Population and Housing Census 1994 – Oromiay Region Analytical Report" (PDF). Addis Ababa: Central Statistics Agency (CSA). p. 37. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "Population and Housing Census 2007 – Oromia Statistical" (PDF). Addis Ababa: Central Statistics Agency (CSA). p. 223. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Census 1994 – Oromiay Region Analytical Report" (PDF). Addis Ababa: Central Statistics Agency (CSA). p. 54. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ a b "Population and Housing Census 2007 – Oromia Statistical" (PDF). Addis Ababa: Central Statistics Agency (CSA). pp. 280–281. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

- ^ "Afaan Oromo". University of Pennsylvania, School of African Studies.

- ^ Shaban, Abdurahman. "One to five: Ethiopia gets four new federal working languages". Africa News.

- ^ a b "The world factbook". cia.gov. 22 November 2021.

- ^ "ቤት | FMOH". moh.gov.et.

- ^ "Children's books breathe new life into Oromo language". BBC.

- ^ "Oromo". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ "Languages of Ethiopia". Ethnologue. 19 February 1999. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

- ^ "Ethiopian Gold Export Soars". ezega.com.

- ^ gold mining companies in ethiopia, n.d.[dead link]

- ^ "Khat is big business in Ethiopia". Deutsche Welle. 10 July 2019.

- ^ "CSA 2005 National Statistics – Tables D.4 – D.7" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2008.

- ^ Deininger, Klaus; et al. "Tenure Security and Land Related Investment, WP-2991". Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 23 March 2006.

- ^ Dambi Dollo University Website

- ^ Mettu University website

- ^ Oda Bultum University Website

- ^ Oromia state university website

- ^ "Oromia zone". oromiyaa.gov.et.

- ^ "sirni hundeeffama Godina Baalee Bahaa". obnoromia.com (in Oromo).

- ^ Central Statistical Agency of Ethiopia (web), 2022: https://www.statsethiopia.gov.et/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Population-Size-by-Sex-Zone-and-Wereda-July-2022.pdf

- ^ The West Guji Zone was created by nine districts and two towns taken from the Borena Zone and Guji Zone. Its area and 2022 population are included in the figures for those Zones.